Early in military service, leaders teach and reinforce the concept of service members showing up to the right place, at the right time, in the right uniform, with a good attitude. This simple method of discipline is so essential to an effective (note not efficient) military organization that it is universal across initial training. In many cases, instructors reinforce this discipline through shared suffering, where an entire organization of individuals pays a hefty price for a single member to fail to meet the standard. Meted penalties highlight the importance of every individual’s contribution to the team to achieve results.

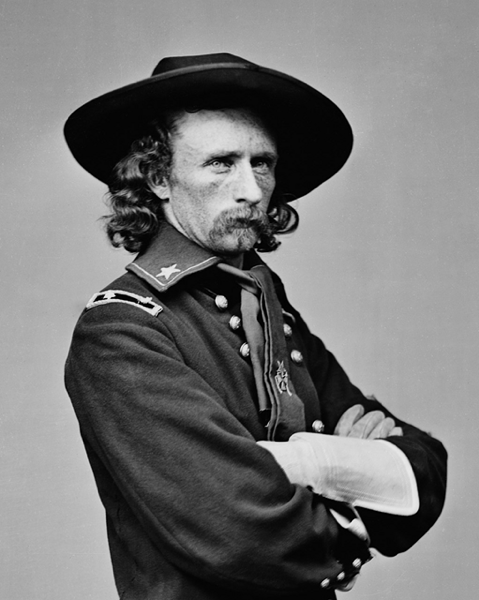

These early lessons manifest themselves in a military operation, where a single individual or small team can derail an entire operation’s synchronization through failure to arrive on time at the right place. History is replete with examples, where such indiscipline affected the outcome of military victory. One such famous example occurred at the Little Big Horn, in Montana when Lieutenant George Custer’s flanking column failed to take its objective, leaving Custer and his column cut in two, without the appropriate intelligence, and heavily outnumbered. Custer severely miscalculated multiple variables. For those miscalculations, he paid with his life and that of many of his Cavalry Troopers. At precisely the right time, misplaced teammates contributed to the 7th Cavalry’s defeat at the Little Big Horn.

General George Custer[1]

Conversely, history provides an example in World War II, when General George Patton arrived at precisely the right time to relieve besieged Allied defenders at the town of Bastogne, Belgium. Had he arrived even a day later, it was possible that German forces would have caused a catastrophe. Patton understood the importance of his positioning and timing, not just to the current battles but also to the entire European campaign. The 101st Airborne Division’s valorous defense and Patton’s relief averted disaster. It created a legend and increased morale for the Allies’ military and civilian populations worldwide.

Patton, Eisenhower, & Bradley at Bastogne, Belgium[2]

While junior teammates and leaders rely heavily on this concept of locating at the right place and at the right time, this becomes much more difficult for leaders and remains applicable to any organization: military, business, government, or non-profit. As most leaders can relate, as I rose in position and responsibility, I experienced much less direction on where to position myself. I had to rely more on my experience, understanding of my operating environment, and prioritization of numerous priorities. I found myself double and triple booked by my staff, junior leaders, and the organizational leaders, to whom I reported. I recognized the organizational strategic initiatives and carefully considered how those initiatives might drive me to position at certain places at certain times. Midway through my career, I watched mentors prioritize and make choices. I noted that a leader’s decision about where to locate created some of the most difficult dilemmas. What was it about this nuanced leadership requirement that yielded organizational effectiveness?

I observed that effective leaders chose their position, selected which meeting to attend, and opted for specific engagements, based on their perception of where they would best influence the best-optimized outcome for the whole organization. I adopted that approach as my seniority and responsibility increased, but it took deliberate planning. It often resulted in locating in situations of discomfort or participating in activities that I did not find particularly appealing. This proved especially true when I commanded the 101st Combat Aviation Brigade in Afghanistan. During that assignment, I led over 3000 Soldiers, flying over 150 aircraft, spread across 13 different locations and thousands of square miles. Some locations had no running water, no heat or air conditioning, or hot food. Some locations included Afghan partners. This proved a very dangerous, high-risk time with significant kinetic combat activity.

As the leader of this large organization, I led and managed risk across all of our functions, which included operations, maintenance, sustainment, and intelligence, among others. I had to answer to multiple military senior leaders, coordinate and build relationships with peers, satisfy thousands of customers, and lead our subordinate organizations. After assessing all of the internal and external requirements, I rapidly realized that I could establish an iterative, predictable rhythm, but it would change to meet requirements almost every day. I tried to position myself in places, where I could have the optimal result. Much of that time included interacting with the many senior military leaders. I served as the organization’s senior leader and senior military leaders expected me to answer their queries. During some of the time, I joined junior Soldiers pumping fuel or performing aircraft maintenance. Often, I found some of the most uncomfortable environments for our teammates and I would show up, to share their suffering. That occurred at a refueling site in 110-degree heat or in the back of an aircraft with a poor heater at 0 degrees. Some of the time, I flew missions, which helped me to understand the operating environment, and interact with our people, and customers. At other times, I positioned for days with a subordinate organization, watching them plan and operate. I never established a perfect proportion for splitting my focus. I continually assessed, planned, and moved to where I thought I could most influence.

For those leaders, who become comfortable with a routine or seek a perfect recipe for apportioning time, this probably disappoints you. Neither approach yields the right solution. Ask yourself where you can have the best influence in the short and long run and put yourself there. Sometimes, that is where you will experience the most discomfort or perform those activities that you do not like to do.

Authored by: Matthew Weinshel, Managing Director

[1] "George Armstrong Custer - Wikipedia". En.Wikipedia.Org, 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Armstrong_Custer#/media/File:Custer_Bvt_MG_Geo_A_1865_LC-BH831-365-crop.jpg.

[2] O'Brien, Joseph. “Battle of the Bulge: Patton Ordered the Priest to Pray for Clear Weather, the Weather Subsequently Cleared.” WAR HISTORY ONLINE, 16 Feb. 2019, https://www.warhistoryonline.com/instant-articles/battle-of-the-bulge-patton-ordered-the-priest-to-pray-for-clear-weather-the-weather-subsequently-cleared.html.